It happens at least once a month on the Saturday afternoon thread devoted to listening to the SiriusXM ’70s on 7 reruns of American Top 40. Sometimes it will be a mid-charter that provokes the comment. Sometimes it will be a major hit, but typically one of the goofy mid-’70s songs that was a lightning rod even then. Eventually, somebody will declare that there must have been payola involved.

There’s a Canadian variant of that discussion. The provocation that led me to it was the daily “greatest Canadian song of all-time” competition staged on social media by Canadian History Ehx podcaster Craig Baird. When Trooper’s “We’re Here for a Good Time” — essentially Canada’s “Margaritaville” – beat out “Suzanne” by Leonard Cohen, followers reacted strongly. One suggested that Trooper wouldn’t have had a career without the Canadian Content regulations that keep radio playing 35-40% Canadian content even now.

It’s sometimes hard for music fans to accept when songs they don’t like become bigger than the ones they do. Sometimes the contempt for songs-one-doesn’t-like can often spread to the people who do like them. It certainly fueled the consumer-press hostility toward radio, at least until writers could segue from stories about radio having too much influence to having less power to set the agenda. The more central music is in your life, the more likely you may be to become indignant about Trooper beating out a national treasure.

Calculating the Lost Factor of hits that no longer endure at radio, and being part of the AT40 threads has shown me that there’s somebody who likes almost every song I don’t, particularly “Broken Wings.” In late 1985, Mr. Mister represented the end of CHR’s heyday and a return to the early ’80s yacht rock doldrums. I was a minority opinion then. Now as somebody who programs music for a Soft AC station, it’s one of the songs (along with “Africa”) that seemingly cannot play too often.

Time doesn’t just soften harder songs. It attaches high-school memories to them, too. I sometimes rate the AT40 songs each week and find it’s hard to channel the annoyance that 14-year-old Sean felt about certain songs. As someone who always bonds with strangers over music and radio, we can probably become friends if you like “Up in a Puff of Smoke” by Polly Brown, but it’s not a requirement. My wife likes Steely Dan more than I do, but I turn them up for her, particularly since she was so understanding about my workout playlist called “Mexican Bubblegum.”

I also take it for granted that my tastes will overlap perfectly with those of almost nobody else. If this were “never have I ever,” the Mexican Bubblegum list would instantly separate me even from most Ross on Radio readers. I’ve also found that ROR readers in general have different tastes. During the Lost Factor series, I was often asked by a reader how a song could be obscure now if they had just heard it on SiriusXM or, in one case, on relatively deep Internet oldies stations. Years of working in music research have shown me that most people don’t hear songs that way.

Those 20 years in music research were preceded by a like number of years working for trade publications. Without arguing the existence of actual payola, I can say that hype — the disproportionate amount of promotional emphasis given to those songs that didn’t seem to be hits — was very much a factor in getting songs to a certain point on the charts, usually mid-to-low 30s, but rarely in bringing them home as true hits. Very few of them are big enough to make the year-end Top 100, although Lost Factor has certainly identified a handful of No. 9 hits that were hyped just enough to be exposed when they were lost to time later.

Lots of factors impact what-becomes-a-hit including available product and what CHR feels like playing at the moment. It’s even more nebulous now that radio has been diminished and the question of “are these really hits” has been amplified. It has never been pure merit. But what would pure merit be? Would it be songs that the entire audience might have liked better under the circumstances? Or are we just back to the songs you like personally?

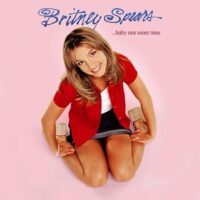

Polarizing hits are the ones most often dismissed as hype. So is anything from the time after somebody stopped liking pop music. I’ve seen older Facebook friends cast aspersions about Britney Spears and teen pop. But having been there in 1998, I can assure you that any hype wasn’t on behalf of Spears, but usually for the veteran big-name artists that she had just made less relevant. Same goes for those goofy ’70s novelties. They usually broke themselves. There was no conspiracy to force “Convoy” on to people who hated it.

When it comes to how songs endure, with the label promotional element removed, there’s a variety of stories. “(I Just) Died in Your Arms” by Cutting Crew, a relative trifle, has become a strangely durable hit song for the ages. “Walking on Sunshine” by Katrina & the Waves — a critically beloved band and personal favorite in the mid-’80s — has started to fade. Not only is Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up” more enduring than any Smiths song, UK audiences seem to enjoy Astley singing Smiths songs more than Morrissey these days.

“We’re Here for a Good Time” benefitted for years not just from Canadian Content requirements but from other radio rules that required a certain number of songs that peaked below No. 40. But the same regulations applied to “Suzanne,” too, and for a minute after the regulations took hold, a now-forgotten cover of “Suzanne” by Tom Northcott became a radio hit across Canada.

As a fan of late-’70s Canadian rock, Trooper is a solid act with multiple decent singles and one rockier anthem, “Raise a Little Hell,” that endures almost as much as “We’re Here for a Good Time.” Meanwhile, it was Cohen’s “Hallelujah” that became the song for the ages. Around the same time, I saw a social-media discussion about whether “Hallelujah” should ever be used (as it now is) as a Christmas song. That one might make an even better (and more mainstream) column, but I’d rather be in the weeds than a minefield.

After a lengthy period in the late ’10s of hit music that I found unbearable, I was surprised to look at the CHR charts this morning and realize that I like nine out of the top 10 on some level and find myself merely indifferent to the 10th. That doesn’t mean that Top 40 is in a good place yet; some of those are songs that I’ve been burnt on for months. And there’s not much depth beyond the top 10, in part because label hype has almost entirely ended (at least when it comes to radio).

Perhaps that means that I should gracefully accept the decisions by TikTok users about what songs have the potential to become hits. Right now, they befuddle me and much of radio. Lesley Gore was a great artist with a surprisingly deep catalog, and users chose her album filler version of “Misty”? But very few of TikTok’s eccentricities have achieved enough critical mass to make the current version of AT40. And at this writing, Universal Music has pulled its product, including Lesley Gore, from TikTok. Radio and the industry still need a better way to determine what listeners really like now. But when they do, I’m willing to abide by the decision.

This story first appeared on radioinsight.com