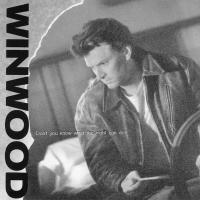

If any song seemed teed up as a hit, it was “Don’t You Know What the Night Can Do” by Steve Winwood. In 1988, Winwood had followed the surprise comeback of his Back in the High Life album with a No. 1 song, “Roll With It.” Michelob was already using the new song in TV ads, tagging it in advance as the next “Tonight, Tonight, Tonight”-type sync, back when TV-tie-ins were unicorns, not ubiquitous.

If any song seemed teed up as a hit, it was “Don’t You Know What the Night Can Do” by Steve Winwood. In 1988, Winwood had followed the surprise comeback of his Back in the High Life album with a No. 1 song, “Roll With It.” Michelob was already using the new song in TV ads, tagging it in advance as the next “Tonight, Tonight, Tonight”-type sync, back when TV-tie-ins were unicorns, not ubiquitous.

I hope we can agree that “Don’t You Know What the Night Can Do” did not become “Tonight, Tonight, Tonight.” Like a lot of songs by veteran artists as the hits became more rhythmic, it never became a large-market record. I don’t remember hearing it much on WHTZ (Z100) and only a little more on WWPR (Power 95, a/k/a WPLJ). I made a lot of radio road trips, and I don’t recall it much even there.

But was it a hit? I’ve always grouped that song with superstar flameouts like “How Much Love” by Leo Sayer or “Boogie Child” by the Bee Gees, songs that followed No. 1 hits, roared out of the gate with the support of major-market radio, and then disappeared. That’s why I sent this tweet:

Winwood was a sure-fire sync-driven hit that turned out not to be. Escape Club was the surprise hit. In between was the game-changer. https://t.co/68GPmQtteA

— Sean Ross (@RossOnRadio) August 21, 2022

That prompted two different readers to ask how I could say that about any song that had gotten to No. 6 on the Billboard Hot 100?

Respectfully disagree…!

Night got to #6 … and had already become a pop culture staple thanks to the Michelob ads…

Come on…. that’s a hit. pic.twitter.com/bFY2u5ZZtR— SteveBunin (@SteveBunin) August 21, 2022

On Facebook’s Billboard Chart Floppers group, a lot of similar discussions have taken place over songs that went top 20 — the group’s cut-off point — but seem more obscure now. After several years, there are fewer disputes, but one recent example was “Cry” by Godley & Creme. That song was No. 16 in 1985, but certainly disappeared quickly and feels lost now. It got five spins last week. Coldplay’s “Clocks,” only No. 29 at the time, was also posted in the group this week. It got 445 spins last week.

We know that songs don’t endure evenly. That’s why Ross On Radio’s Lost Factor series has been so much fun over the last two years. (I calculated 4,000 songs; perhaps 500 get significant spins now.) We also know that failure to endure does not mean that a song was never a hit in the first place. You can’t take “Physical” away from Olivia Newton-John, or even the far-more-“lost” “Make a Move on Me.” Having a catalog reduced to one song at radio doesn’t make Rick Springfield a one-hit wonder … or Aretha Franklin. (And if you lived in Milwaukee or Minneapolis, I’d allow that you experienced the Winwood song as a hit, even if radio there ignores it now as well.)

We spend a lot of time wondering “what’s a hit” in 2022, with listening patterns in flux and radio’s hegemony long gone. We know that “We Don’t Talk About Bruno” was a phenomenon, but without securing radio in a big way, it now feels safe to say that it never had the footprint that you would have once expected from a five-week Hot 100 No. 1. As we look to declare the Song of Summer 2022 this week, we can look forward to numerous articles about how it’s no longer the shared experience of old.

Stereogum’s Tom Breihan backed away from the discussion of “what does No. 1 on the Hot 100 mean anyway?” rather than engage any further with angry BTS fans. But as his The Number Ones series moves into the late ’90s/early ’00s, he’s already writing about songs that prompted that same discussion decades ago, particularly Mariah Carey’s “Thank God I Found You” and R. Kelly & Celine Dion’s “I’m Your Angel.” I feel safe in saying that the industry consensus view was that those songs weren’t hits at the time, but technically they were even bigger than Winwood. Perhaps they have their defenders, too.

Perhaps the lowest setting of the bar is Canada’s broadcast regulator. For many years, Canada’s FMs were required to play more than 50% music that was “non-hit,” meaning that it had peaked at No. 41 or lower in the U.S. or Canada. Songs that became hits retroactively, of the “I Melt With You” sort, were golden for programmers. So were songs that were never singles, which meant that the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun” counted as a non-hit. But their version of “My Bonnie (Lies Over the Ocean),” which reached No. 26 at the height of early Beatlemania, did not. Again, I feel safe in saying that No. 40 is too low, but if you’re, say, Gunhill Road, whose only chart single peaked at No. 40, you might disagree.

If you listened to American Top 40 when “Back When My Hair Was Short” was on the charts in 1973, or if you listen to the current weekend reruns, you might disagree, too. Some of those songs existed for chart fans and ROR readers far more than they did for most people. The catch is often that some songs that read as hits to one listener are the ones that prompt the “what the hell is this” tweets from others in the Saturday afternoon #AT40 group. “Ariel” by Dean Friedman — polarizing anyway — is always new to a few listeners each time. But on WPST Trenton, N.J., it was a fixture in the evening Top-3 countdown and a discussion topic at my high-school lockers the next morning.

AT40 tweeters sometimes end up discussing the flakiness of the charts in 1974-75, with their turnover at No. 1 and precipitous drops from the top slot. In 1988, there was again the distrust of the charts that would create the need for verified sales and monitored airplay. This was especially the case for big-name artists with follow-up juice from previous hits or earlier projects. (Chris Molanphy writes about this at length, especially with albums.) I don’t think of Winwood as a hit because I feel the same way about “Perfect World” by Huey Lewis & the News, and that went to No. 3 around the same time.

Here’s a reverse hierarchy of whether I think of a song as a hit at the time:

I heard it on a regular basis on the radio for a period of a few months. 1985’s “King for a Day” by the Thompson Twins is a good example. It’s not a song you hear now, but my memory of hearing it on one road trip after another at the time is confirmed by it having gone to No. 8. But I also remember the top-20 “Life in One Day” by Howard Jones the same way. So it’s not a perfect measurement.

It gained, rather than lost momentum — or at least grew steadily. Years later, “Bette Davis Eyes” remains a favorite example of a song that went from “this is kinda different for Kim Carnes” to “this is a smash.” But even Lizzo’s “About Damn Time” exceeded expectations as the weeks went on this summer, in part because “Rumors” had taken the opposite path last summer. By the time “Don’t You Know What the Night Can Do” got to No. 6, it was thought of in the industry as a “work record.”

It went to power rotation. There are a few hits of the “Physical”/“You Light Up My Life”/“One Bad Apple” variety that were lost (hidden, really) later on. More often, our Lost Factor analyses have found a lot of songs that peaked in the lower reaches of the top 10. Those are the turntable hits that loom larger for their radio-programmer champions or chart fans who were paying closer attention. Going to recurrent was also a pretty good indicator.

People who didn’t follow pop music were somehow aware of it. In the ’80s, this often translated to “your parents and their friends with no particular interest in pop or rock music of any sort.” That might be a less-reliable indicator now. The mother/daughter coalition I dismiss as completely dismantled now — at least when it comes to new music — might actually be a coalition of two, sharing some indie-rock or Tik Tok rap favorite, but perhaps even aware of our Song of Summer contenders. But as recently as the late 2000s, when “bringing SexyBack” jokes were everywhere, it was a reliable indicator.

As with Lost Factor in general, I’m glad when ROR readers enjoy this discussion. Music is personal and choosing to remember a “hit” is not just lower but likely personal as well, at least among ROR readers. When people stopped arguing about why “radio sucks for not playing __________,” it meant that enough listeners had access to that unnamed act or genre to not care about radio. At a moment when we don’t have many hits, and some argue that we never again will, I hope we continue to care what the hits are, and were, as well.