Editor’s note: I first wrote this story five years ago, already after the Marvin Gaye estate had already won a judgment against “Blurred Lines.” I’m republishing it now that the estate of Gaye’s co-writer Ed Townsend is in court with Ed Sheeran.

Editor’s note: I first wrote this story five years ago, already after the Marvin Gaye estate had already won a judgment against “Blurred Lines.” I’m republishing it now that the estate of Gaye’s co-writer Ed Townsend is in court with Ed Sheeran.

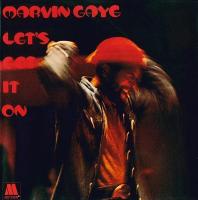

This is a story about piecing together the connections between songs, sometimes many years later. For what it’s worth, “Thinking Out Loud” has never made me think of “Let’s Get It On,” even aided. But this song does. “Finally Got Myself Together” was an R&B and minor pop hit for the Impressions a year later. Townsend wrote it, and he certainly had the right to employ a sound he helped create. But his “Let’s Get It On” co-author Gaye is not credited here. It was a different time. Here’s what I wrote at the time (including a Gordon Lightfoot reference).

I went to see Three Dog Night. My wife says I’ll go see any heritage band that can still stand up, although in this case, we went because a friend had a connection to the opening act. But they were good. Cory Wells had passed. Chuck Negron had left the group. Fortunately, this was the band with three lead singers. Danny Hutton could still hit a lot of high notes, and they were generous about going deep in to the catalog — “Let Me Serenade You,” “Liar,” “The Family of Man,” and in particular, “Sure as I’m Sittin’ Here,” the John Hiatt song that was one of their last semi-hits.

I heard that version of “Sure as I’m Sittin’ Here” a few times in fall ‘74, and not much thereafter. Hearing it this time, something new came to me. I realized one of my favorite country records of all time — a country-only hit from several years later — had a lot in common in terms of both lyrical structure and melody with “Sure as I’m Sitting Here.” Except for the country song’s guitar solo; that was clearly influenced by a much bigger pop hit that was out at almost exactly the same time as the Three Dog Night single.

I’ve always enjoyed the moment of recognition of making the connection between songs. And it’s been happening a lot lately. Australian radio veteran Brent James sent me one of his Australian compilations CD of ’70s pop. In the course of listening to just one of its discs, with 20 songs, I had at least 3-4 new “this sounds like this” moments. Some were just songs with little similar flourishes or a line here and there. Others had a similar feel throughout.

Some were reasonably well-known songs and maybe I just hadn’t thought about their similarities for a while — e.g., the turboed-up bluegrass of both Ray Stevens’ “Misty” that laid a base for Glen Campbell’s “Southern Nights” 15 months later. Some were songs I’d heard once or twice. Suddenly, I could hear that an early ‘70s obscurity by Ohio Express, “Cowboy Convention,” was the connection between both the Cowsills’ ’60s hit “Indian Lake” and a Euro-oddity called “Bulldozer” by Oliver Onions a few years later.

You can often confirm these connections between songs by their timing. I’ve written before about Carl Douglas, “Run Back” –a British hit exactly a year before the Bee Gees’ “Tragedy.” James’ CD had a Cliff Richard song I didn’t know, “Hey Mr. Dream Maker,” but you could tell by overall feel it was within a year of Sammy Johns’ “Chevy Van.” (In this case, it turned out that “Chevy Van” was first — by about 15 months, as it happens.) Then again, I just went back to the Cliff Richard song and this time I heard this Canadian hit from the early ‘70s. You can certainly get lost in the “this sounds like this” game.

There’s also the issue of which observations to share publicly — especially in this more litigious era, after the successful lawsuit against Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” on behalf of Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up.”

I’m hesitant to tell you the country song that I think is copped from “Sure as I’m Sitting Here.” I doubt it made anybody a ton of money to begin with. I’m hesitant to create trouble for the author, who as best I know, is just another member of the entertainment middle class. Plus, there’s a 95% chance that you don’t know both songs, unless you were really following Country in the late ‘70s. (But, if you have somehow already guessed what song I’m referring to, let’s definitely be friends, and hang out, and go on family vacations together with spouses and kids.)

Over the years, I’ve shared my “this sounds like this” observations with two music-industry friends whose own copyrights were on the receiving end of seeming infringement. One pursued a claim. One shrugged it off. People feel differently about this issue, even when it’s their own songs, and you never know who kept their publishing anyway.

Besides, I am always surprised by which similarities between songs are and are not ratified by either the clearance process or lawsuits. The referencing of one line from “Busting Loose” resulted in Chuck Brown having a writing credit on Nelly’s “Hot in Herre.” But 90 seconds of “mama-se/mama-sa/ma-ma-kossa” — the primary lyric of “Soul Makossa” — got Manu Dibango nothing from Michael Jackson.

I’ve never known whether to bring it up when I meet the artists involved. In the early ‘90s, I had a very pleasant but perfunctory meet-and-greet with a prominent Country artist I admired. I figured that this artist would not appreciate me saying, “I liked that new song you did tonight, and I can tell we are both fans of the same lesser-known Gordon Lightfoot song.” But wasn’t that supposed to be a secret handshake? Shouldn’t fans of a given artist find each other and bond over music?

As with a recent series of articles on the various mystery songs that I hunted down over the course of many years, I’m never quite sure whether to reveal this level of geekery to the public. Will you view it as obsession? Or super-power? But enough people responded to that article to further confirm that I was not alone. And I’m not the only one. A few days ago, a radio friend e-mailed a group of several people. “Which ’70s song does 5 Seconds of Summer, ‘Youngblood,’ remind you of?” Another friend shot back “Gold” by John Stewart before I could even think about it. People out there turned “Gold” into gold.

Why am I hearing so many song connections now after all these years? Is my sense of song recognition getting sharper as other middle-aged synapses become less reliable? To some extent, I think it’s hearing these songs in a different context now. Artists have always had inspirations, conscious and otherwise. Pop music always goes through phases. By the time you hear a second hit that is perhaps influenced by a first, there have been nine months of other songs in a sort of similar vein on the radio. Hearing songs now out of the context of that period’s hit music is to be able to focus on the details more. And as the streaming era follows the iPod age, every song in pop-music history is on the buffet table to consume.

Another realization that I’ve had is that song-to-song similarities stand out less during golden ages, or even bronze ages for pop music. The spring ’75 months surrounding “Chevy Van” were not a high point for most. And yet, the much-vaunted variety that people remember about Top 40 from that era was still in evidence. If the charts were heavy with MOR that spring (Paul Anka, Carpenters, Barry Manilow, Frankie Valli’s “My Eyes Adored You”), there was also Grand Funk and Queen; Ohio Players and B.T. Express; Linda Ronstadt and the Eagles. Horizontal variety takes the onus off of vertical similarity.

All of which puts the homogeneity of today’s pop music into perspective. Daring to suggest that “everything sounds the same” is prime evidence of losing the groove and one’s relevance in the music industry. I feel a little freer to criticize the current hits since there’s safety in numbers. Suggesting that there’s a lot of 85-bpm EDM trap pop with chopped-up vocal samples is not merely my observation now, and the ratings of Top 40 radio prove that the kids don’t necessarily get it.

And now maybe it’s time to consider this contrarian explanation. Perhaps the ability to hear similarities between songs is not a matter of losing discernment but gaining it with time and seasoning. People judge the music they hear in high school through a gauzier filter; if you’re class of ’75, you almost certainly remember “Chevy Van” with a more genuine appreciation than anybody else. When it’s music of your golden age, you enjoy hits, good and bad, and you enjoy the hits that sound like other hits. With time, you judge music with more sophistication, and that applies to being able to see similarities as well.

This story first appeared on radioinsight.com